Teacher Portal

Investigation 2: Concepts

Meiosis and Gamete Formation

Navigate:

Once the slide presentation is launched

- use your left and right arrows to advance or go back in the slide presentation, and

- hover your mouse over the left edge of the presentation to get a view of the thumbnails for all the slides so that you can quickly move anywhere in the presentation.

- Click HERE to launch the slide presentation for the CELL.

SLIDE HPD-2-1

Welcome to Investigation 2 of our unit on Human Prenatal Development. In this Investigation, we’re going to follow the amazing journey from: a single fertilized egg (a zygote) to an embryo, to a growing fetus.

You’ll learn how genetics, cell division, and fetal development work together to form a completely new human being.

In this Investigation, we’ll focus on:

- How meiosis produces sperm and egg cells

- How fertilization creates a unique individual

- And how that zygote grows and changes over time

You’ll also continue our “Modeling the Miracle” lab activity, where you’ll build and measure models that represent the fetus at different stages of development.

Discussion Questions and Answers:

Q1: What are we going to learn in this investigation?

A1: We’ll explore how a human develops from a fertilized egg, through the stages of embryo and fetus, all the way to birth.

Q2: Why is it important to learn about prenatal development in science class?

A2: It helps us understand how life begins, how the body forms, and how biology plays a role in every person’s development.

Q3: What does “prenatal” mean?

A3: “Prenatal” means “before birth.” It covers everything that happens while the baby is still growing inside the womb.

SLIDE HPD-2-2

Your genotype is like your genetic recipe. It’s the set of instructions in your DNA that tells your body how to grow, what color your eyes might be, how tall you could become, and more.

You get half of your genes from your mother and half from your father. Your phenotype is what actually shows up—the traits you can see or measure. Examples include eye color, hair color, whether you have freckles, or if you’re right- or left-handed.

Think of it this way:

Genotype = genes

Phenotype = what you see

Even though your genotype stays the same, your phenotype can be affected by both genes and the environment—like how sunlight can make your hair lighter!

Discussion Questions and Answers:

Q1: What does genotype mean?

A1: Genotype is the set of genetic instructions in your DNA. It determines the potential traits you inherit.

Q2: What does phenotype mean?

A2: Phenotype is the visible or measurable trait that actually appears—like eye color or height.

Q3: Can your environment affect your phenotype?

A3: Yes! The environment can influence how some traits appear, even if the genes stay the same. For example, sunlight can lighten your hair.

SLIDE HPD-2-3

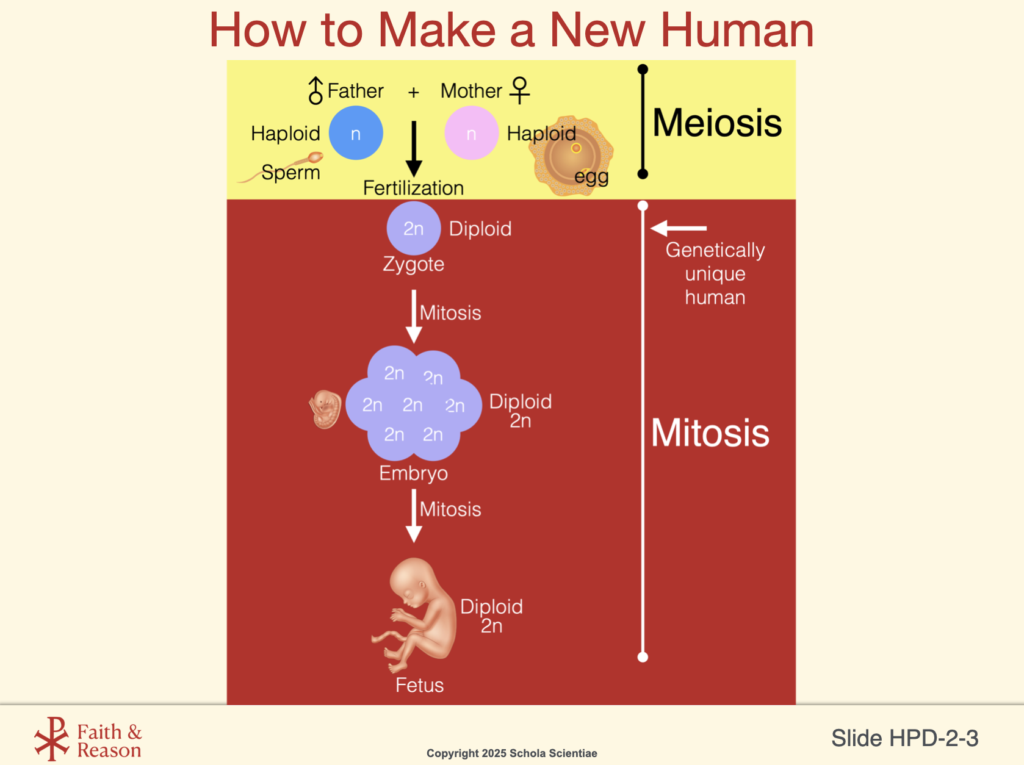

Let’s walk through how a new human begins—using science and cell biology.

Start with meiosis: The father makes a sperm cell, and the mother makes an egg cell. These are called haploid cells, which means they each have n chromosomes (half the usual number).

Fertilization: When a sperm and egg join, they form a zygote—this is the very first cell of a new human. It now has 2n chromosomes, meaning it’s diploid (a full set of DNA—half from mom, half from dad).

Next, mitosis takes over: The zygote starts to divide by mitosis, making more cells that are all diploid.

This forms the embryo—a cluster of growing cells, all with the same 2n genetic code. More mitosis = more growth: As the embryo keeps dividing, it becomes a fetus, and continues developing into a baby.

Key terms to remember:

- Haploid (n): Half set of chromosomes (sperm and egg)

- Diploid (2n): Full set of chromosomes (zygote, embryo, fetus)

- Zygote → Embryo → Fetus = stages of early human development

Meiosis makes the sperm and egg. Mitosis grows the human from one cell to trillions!

Discussion Questions and Answers:

Q1: What is the difference between meiosis and mitosis in this process?

A1: Meiosis creates gametes with half the DNA (haploid), while mitosis helps the fertilized egg grow by making identical diploid cells.

Q2: What is a zygote?

A2: A zygote is the very first cell of a new human, formed when a sperm and egg unite. It is diploid (2n).

Q3: What happens after the zygote forms?

A3: The zygote divides by mitosis to create more cells, becoming an embryo, and later a fetus.

SLIDE HPD-2-4

Let’s take a quick look back at mitosis, which you’ve already learned: Mitosis is a type of cell division responsible for growth and tissue repair.

You start with one diploid (2n) cell. After mitosis, you end up with two identical diploid (2n) cells.

The steps are: Prophase → Metaphase → Anaphase → Telophase

Each new cell gets the exact same DNA—like making a perfect photocopy.

Here’s the cool part: The first half of meiosis (called Meiosis I) follows steps that look a lot like mitosis! Same basic idea. Similar stages. Same cell machinery. So if you understand mitosis, you’re already halfway to understanding meiosis!

There’s just one important difference coming up… and we’ll look at that in the next slide. It’s called crossing over, and it helps make sure that no two humans (except identical twins) are ever exactly the same.

Discussion Questions and Answers:

Q1: What is the purpose of mitosis in the human body?

A1: Mitosis allows your body to grow, repair injuries, and replace old or damaged cells.

Q2: How many cells are produced in mitosis, and are they identical?

A2: Mitosis produces two identical diploid cells, each with the same DNA as the original.

Q3: How is mitosis related to meiosis?

A3: The steps of Meiosis I look very similar to mitosis—but meiosis creates four unique cells with half the DNA, not two identical ones.

SLIDE HPD-2-5

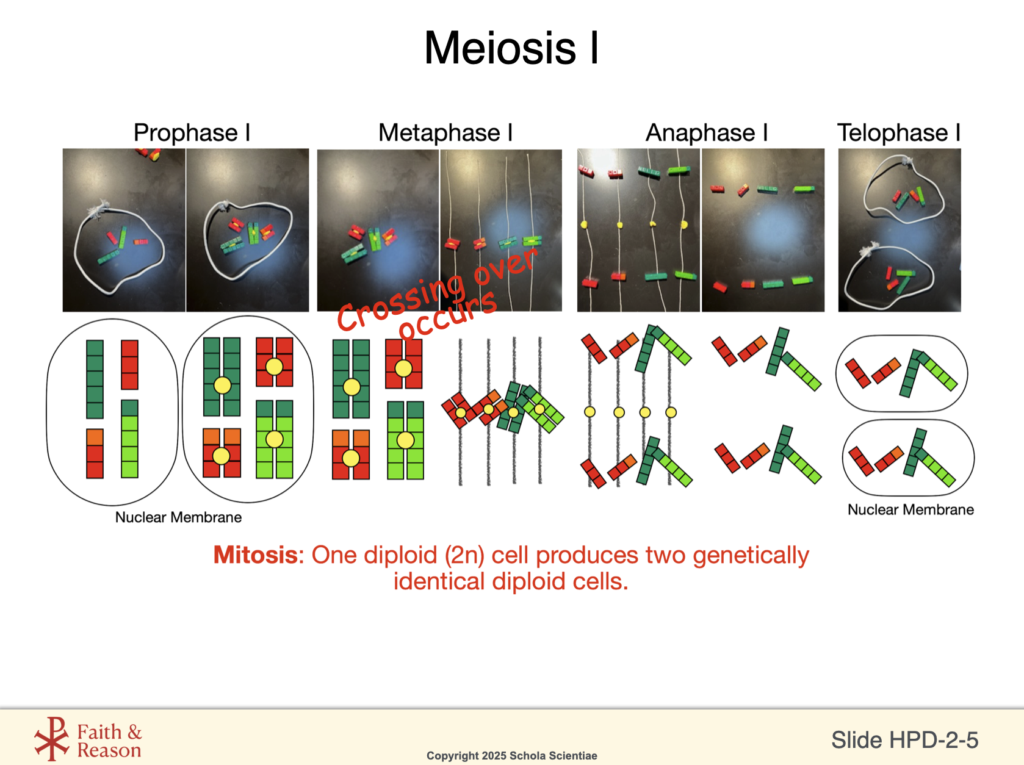

This slide might look a lot like the mitosis review we just saw—and that’s no accident!

In Meiosis I, the steps still go: Prophase I → Metaphase I → Anaphase I → Telophase I

Just like mitosis, the chromosomes line up, get pulled apart, and end up in two new cells. BUT… there’s one very important difference happening here—see that red writing? During Metaphase I, something called crossing over can happen. This is when chromosomes swap little pieces of genetic material. What does that mean? It means that each chromosome becomes a mix of Mom and Dad’s DNA—a totally unique combination.

At the end of Meiosis I: We still have diploid cells (2n), but the DNA inside them is now mixed up, making every future sperm or egg cell different.

Discussion Questions and Answers:

Q1: What is Meiosis I mostly responsible for?

A1: Meiosis I separates pairs of chromosomes and mixes genetic material through crossing over.

Q2: What makes Meiosis I different from mitosis?

A2: In Meiosis I, homologous chromosomes pair up and can exchange pieces (crossing over), creating genetic diversity.

Q3: Why is crossing over important?

A3: It increases variation by mixing traits from both parents, so each gamete (and each person) is genetically unique.

SLIDE HPD-2-6

This is the whole meiosis process—from start to finish!

Meiosis I (Top row): You start with one diploid (2n) cell. Just like in mitosis, the chromosomes are copied and pulled apart. But during Metaphase I, chromosomes from Mom and Dad mix and match a little (crossing over). At the end of meiosis I, you get two diploid cells, but they’re not identical anymore.

Meiosis II (Bottom row): Now each of those two cells goes through a second round of division. But this time, there is no DNA copying—no replication before the split. The goal here is to split the chromosomes in half.

By the end of Meiosis II, you’ve made four cells, each with half the DNA—these are haploid (1n) cells. These are the sperm or egg cells, also called gametes.

Bottom line: Meiosis starts with 1 cell and ends with 4 unique cells. Each has half the DNA, and they’re all different from each other. That’s what makes you uniquely you!

Discussion Questions and Answers:

Q1: What’s the final result of meiosis?

A1: Four genetically different haploid cells (gametes), each with half the DNA of the original cell.

Q2: What happens between Meiosis I and Meiosis II?

A2: The two diploid cells from Meiosis I go straight into Meiosis II—no new DNA is copied in between.

Q3: Why is it important that gametes only have half the DNA?

A3: So that when a sperm and egg unite at fertilization, the new zygote ends up with a full set of chromosomes (46 total in humans).

SLIDE HPD-2-7

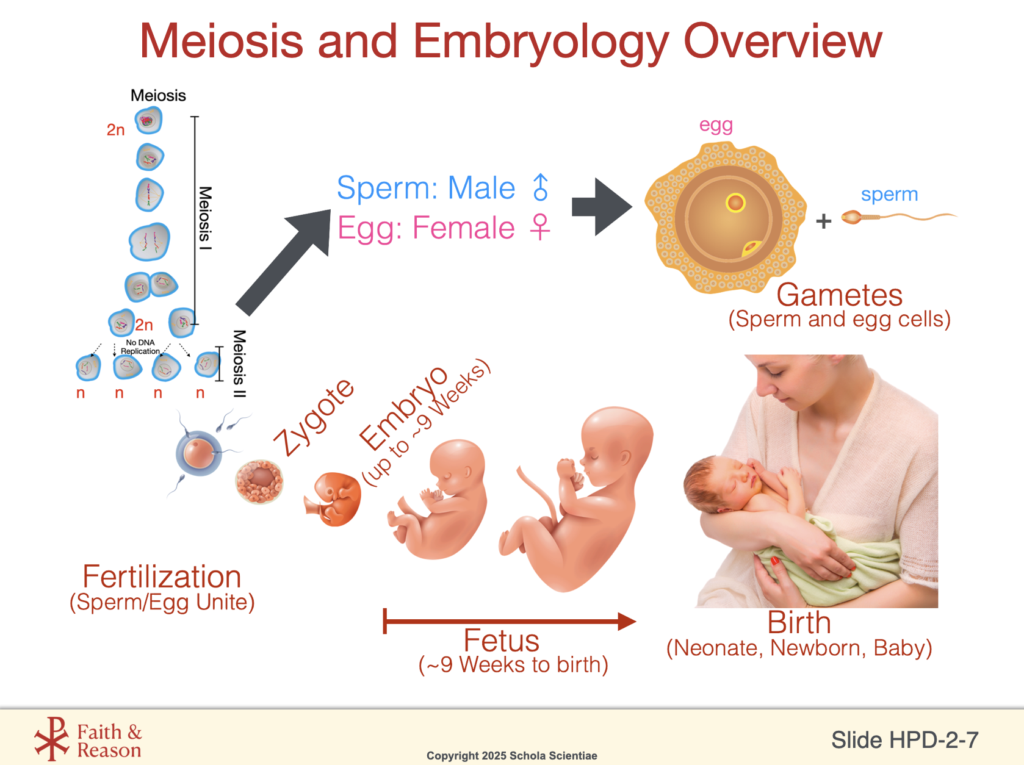

Let’s zoom out and look at the entire process of how a new human begins:

- Meiosis (on the left) is how gametes—sperm and egg cells—are made.

- Each gamete has half the DNA (haploid, or n).

- After Meiosis I and II, we get 4 unique cells, ready for fertilization.

- During fertilization, a sperm cell (from the father) and an egg cell (from the mother) unite to form a zygote—the very first cell of a new human life.

- The zygote begins dividing and growing, becoming first an embryo (up to about 9 weeks), and then a fetus until birth.

Scientific Note on Sex Determination: Each parent contributes 23 chromosomes to the baby. One of those pairs is the sex chromosomes:

- The mother always gives an X chromosome.

- The father can give either an X or a Y.

- So, the father’s sperm determines the biological sex:

- X from father + X from mother = female (XX)

- Y from father + X from mother = male (XY)

That’s just how the science of chromosomes works—simple and elegant!

Discussion Questions and Answers:

Q1: What is the role of meiosis in reproduction?

A1: Meiosis creates gametes—sperm and egg cells—that have half the DNA needed for a new human.

Q2: What happens during fertilization?

A2: A sperm and egg combine to form a zygote, restoring the full set of chromosomes.

Q3: How is biological sex determined?

A3: The sperm decides sex: an X sperm leads to a girl (XX); a Y sperm leads to a boy (XY).

SLIDE HPD-2-8

Let’s bring everything together: When a sperm and egg unite during fertilization, the baby’s genetic sex is set immediately. Every egg from the mother carries an X chromosome. Sperm from the father can carry either an X or a Y chromosome.

That means: X + X = XX = female and X + Y = XY = male

The father’s sperm decides the sex of the baby, based on which chromosome it carries. This is a simple, elegant example of how our DNA shapes who we are—from the beginning!

Discussion Questions and Answers:

Q1: Who determines the biological sex of the baby—mother or father?

A1: The father—because only the sperm can carry either an X or a Y chromosome.

Q2: When is the baby’s biological sex determined?

A2: Immediately at fertilization, when the chromosomes from sperm and egg combine.

Q3: Can we tell if a baby will be male or female by looking at the egg?

A3: No. All eggs carry an X chromosome. Only the sperm varies (X or Y).

SLIDE HPD-2-9

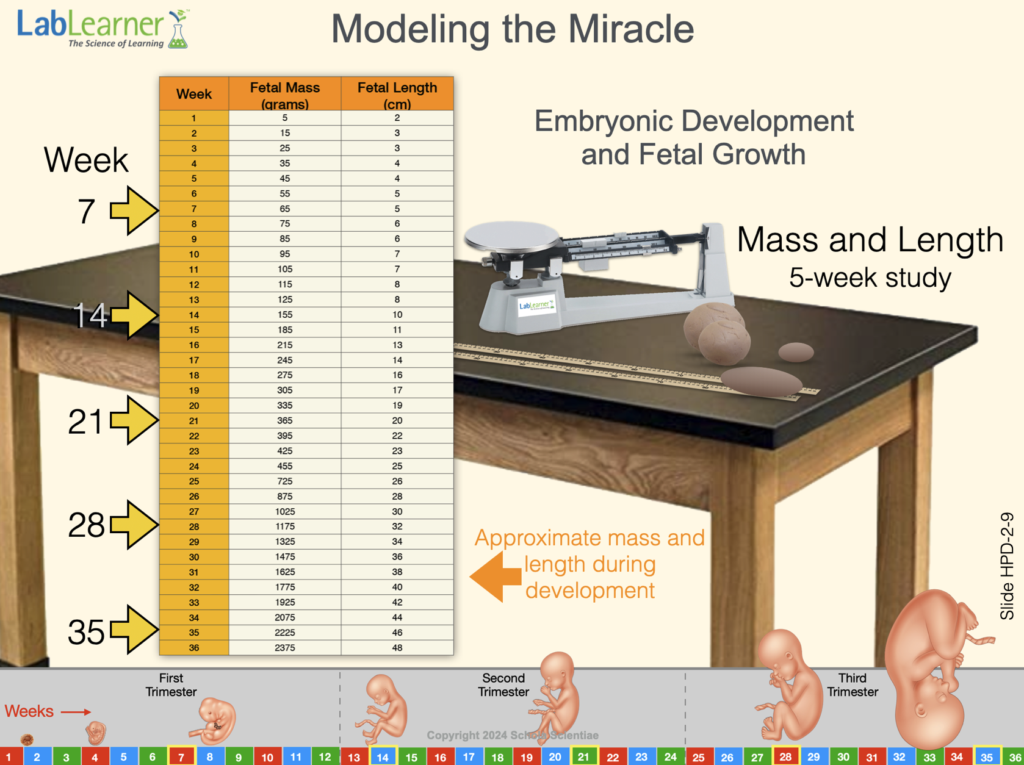

This week, you’ll continue the Modeling the Miracle activity you started in Investigation 1. Last time, you modeled an embryo at 7 weeks. That was during the first trimester, when development is just getting started.

Now you’ll model a 14-week-old fetus—right at the start of the second trimester.

Look at the chart:

- In just 7 weeks, the fetus has grown from 5 cm to 11 cm, and from 5 grams to 185 grams.

- That’s a huge increase in size—and it’s just the beginning!

Your job in lab is to:

Model the shape and mass of a 14-week-old fetus using clay.

Measure and record the mass and length accurately.

Compare your new model to the one you made for 7 weeks—and observe the difference.

You’ll do this again later for Week 21 and Week 28, so by the end of the unit, you’ll have a nearly full timeline of fetal growth that you’ve modeled yourself. This activity helps you see how rapidly the human body develops—and how biology can be measured, modeled, and understood step by step.

Discussion Questions and Answers:

Q1: What does this activity help us understand?

A1: It shows how quickly a human fetus grows during pregnancy and makes that growth easy to see and measure.

Q2: Why do we use clay models in this lab?

A2: Clay lets us shape and scale the fetus by mass and length, helping us visualize real fetal development.

Q3: What trimester is the 14-week fetus in?

A3: The second trimester is just beginning at Week 14. The fetus has grown a lot since Week 7.

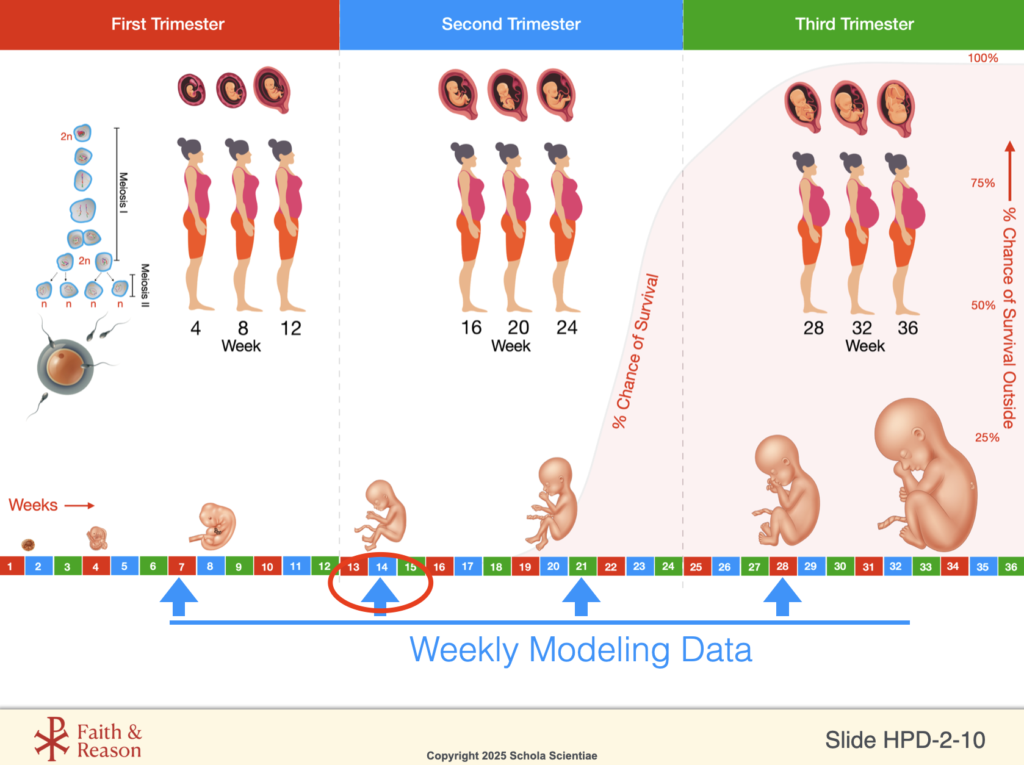

SLIDE HPD-2-10

Let’s look again at the timeline of fetal development—but this time, we’re adding something new: The chance that a fetus could survive outside the womb.

This week in lab, you’re modeling the fetus at 14 weeks. As you can see, that’s still in the second trimester, and based on the survival curve on the right—it’s well before the point of viability.

Why can’t a fetus survive this early? Here are a few key reasons:

- Lungs aren’t ready to breathe air—surfactant, which helps lungs stay open, hasn’t developed yet.

- The brain and nervous system are still too immature to control vital body functions like breathing and temperature.

- The fetus is still very small, with underdeveloped skin and organs that can’t function independently.

As you can see, your Week 14 model is still far before the point where survival is possible.

But notice what happens by Week 28 or 29—the chance of survival outside the womb rises quickly. That’s because key systems like the lungs, brain, and immune system are much more developed by that time.

Discussion Questions and Answers:

Q1: Why can’t a fetus survive outside the womb at 14 weeks?

A1: The lungs, brain, and other organs aren’t developed enough to work on their own yet.

Q2: When does survival become more likely if a baby is born early?

A2: Around Week 28–29, when lungs and other systems are more developed.

Q3: What does this survival curve show us about prenatal development?

A3: It shows that the body develops in stages, and that time in the womb is essential for systems to become fully functional.